In the beginning was the telegraph. It started with human operators manually sending messages in Morse code but in time, technological evolution led to automatic teleprinters using codings such as Baudot code and ultimately ASCII, the latter growing out of the desire to support upper and lower case letters as well as numerals and punctuation.

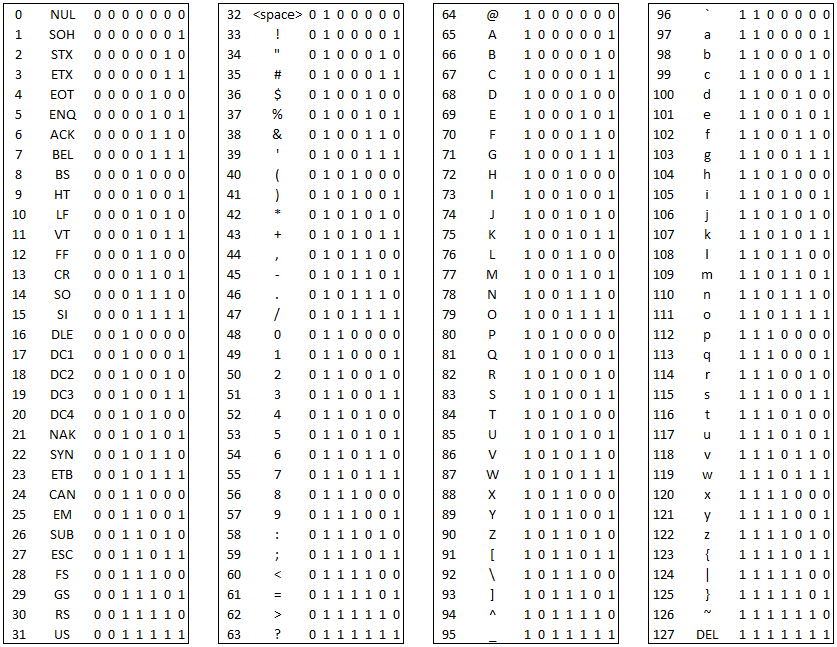

ASCII coding is actually very clever. It uses 7 bits to encode a total of 128 ‘characters’ including control characters (for the teleprinter or end display device) as well as actual characters for display. The structure of the encoding is what’s interesting though. All the control characters (with the exception of DEL) start with the bit sequence \(00\). This means that it’s easy to check whether a character is printable or not, you just have to check bits 6 and 7 for 0. Also, the letters of the alphabet are all encoded in sequence starting with ‘A’ at 65 (\(1000001\)). Then ‘B’ is \(1000010\), ‘C’ is \(1000010\), etc. So if you mask bit 7 then you get direct access to the position of the character in the alphabet. Then the lowercase letters start with ‘a’ at 97 (\(1100001\)) and you can see the same sequence but with bit 6 set to 1 as well. To shift from uppercase to lowercase is a simple bit flip (the equivalent of adding or subtracting 32). Finally, the numerical digits start with ‘0’ at 48 (\(0110000\)) and then run consecutively through ‘9’ at \(0111001\), and again we see that by masking bits 5 and 6 we just get the actual binary values 0 - 9. DEL is an interesting character. It’s not a control character meant to indicate that the user typed the key to delete the previous character, that’s Backspace (with code 8). Rather DEL is a way to void out an existing character that may have been stored somewhere. A good example of this is when punched cards would have been used to store data to be used in mainframe batches. To void out a character (indicated by a pattern of holes punched in a column on a card) you just had to punch out all the holes, effectively making that character deleted, i.e. ‘DEL’ (\(1111111\)).

Here’s the table:

So far, so good … for the English speaking world at least. But what about countries that used additional characters in their alphabets? They developed their own encoding systems of course. The arrival of the computer age, and the fact that systems processed data in 8 bit chunks (bytes), helped in that now a character would be represented as an 8 bit pattern and so 256 different values could be stored. ASCII was naturally extended and the values 128 - 255 were used to store additional characters. Different regions of the world chose to use this extra space differently though and thus was born the idea of codepage where a byte was interpreted relative to any one of a number of different lookup tables in order to determine what character it actually represented. Most codepages used exactly the same bit patterns to encode the standard ASCII character set but they all used the patterns with a leading 1 bit (values above 127) differently. The Latin-1 codepage (aka ISO/IEC 8859-1) was used widely in Western Europe since it contained all the characters needed for those languages. Other codepages were created to accommodate the cyrillic and other alphabets. In countries like Japan, China and Korea - whose languages contained way more glyphs than could be encoded in a single byte - multibyte \encoding schemes were invented. Often these were still compatible with ASCII but the byte values above 127 were used to indicate a shift into a different page where the following byte value was interpreted. This allowed them to encode pretty much all the characters that they needed. Standards proliferated and incompatibilities abounded. It wasn’t so much of a problem in the early days of computing but with the advent of the Internet, and the fact that data generated on one system (e.g. in Japan) could be shared with another system (e.g. in France), the incompatibilities were brought into stark relief.

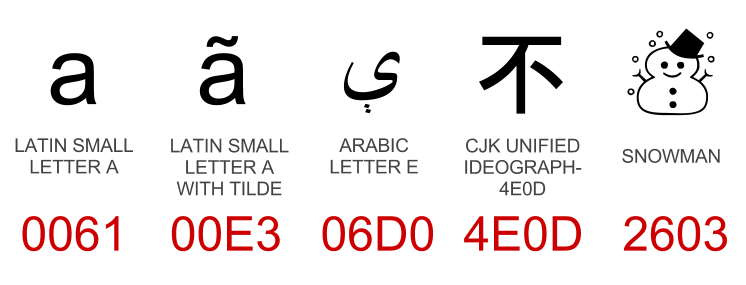

Things could be made to work via clever switching of codepages but it wasn’t pretty. A new standard was needed. An industry working group was formed called the Unicode Consortium and, via a minor miracle, they managed to create a new, all encompassing standard called, unsurprisingly, Unicode. In very simple terms Unicode is a big table that assigns a unique number (a Unicode code point) to all characters. The Unicode standard actually includes a lot more than that though: rules for character collation and other essential matters such as support for right to left text; but for our purposes we can think of it as character = unique number. The code point is just a number now, how it is stored in computer memory is another matter.

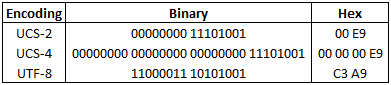

Initially computer vendors implemented Unicode by storing all characters using either two or four bytes. These two schemes were known as UCS-2 and UCS-4 respectively (UCS = Universal Character Set). There were a few problems with this approach though. Firstly, the vast majority of the textual data stored on computers around the world was English and using two (and especially using four) bytes per character, to store data that was mostly just ASCII, was incredibly wasteful. UCS-4 encoded files were four times the size of the equivalent ASCII files. Secondly, the C programming language had introduced the concept of the null terminated string (commonly called C strings) whereby string data was stored as an array of bytes (characters) with the end of the string marked by a null byte. This assumed string structure was baked in to a “lot” of code, and that code was now incompatible with strings stored as arrays of UCS-2/4 characters because those character arrays contained null bytes in the middle of the strings. Code written to expect C strings would misinterpret the leading null byte in the UCS-2 encoding of an uppercase letter ‘A’ (ASCII code 65) as an end of string marker.

UCS-2 and UCS-4 were fine for new applications that stored, and interpreted, all strings as arrays of multiple bytes but they were no good for the efficient transmission of character data (because of the bloat) and interaction with legacy APIs (because they broke the C string paradigm). A new encoding was needed.

So along came UTF-8, a variable length Unicode encoding scheme, supposedly designed in an evening on a placemat in a diner. UTF = Unicode Transformation Format. UTF-8 is very clever too.

- The UTF-8 encoding of ASCII is ASCII. Nice. For all the character data out there that fits in that space it just stays the same.

- UTF-8 does not have embedded nulls and so UTF-8 strings can still be considered as null-terminated byte arrays, and thus can be consumed by legacy C APIs.

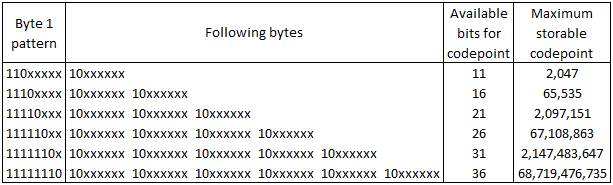

- UTF-8 supports Unicode codepoints above 127 via a variable length byte encoding with the following scheme:

- Notice that the following bytes in a multibyte sequence all start with \(10\). This means that those bytes will never be misinterpreted as ASCII characters.

- Also it’s very easy for code to move forwards and backwards by characters in a UTF-8 string. Simply scan bytes (forwards or backwards) until you find the next (previous) one that starts with something other than \(10\).

Let’s look at an example: é, the lower case acute accented e character, whose Unicode codepoint is 233. This is encoded as follows:

UTF-8 became incredibly popular and I think it’s fair to say that it is now considered the de-facto way for character data to be encoded and exchanged across the Internet. In fact I saw a statistic the other day that stated that now there is more UTF-8 encoded data stored across computer hosts in the world than old codepage encoded data.

For strings stored in memory inside of a given modern application it’s likely that a fixed width character encoding will still be used, for the efficient (offset based) random access to characters that it gives. However as soon as that character data leaves the application domain and is exchanged with another application it will almost certainly be serialized as UTF-8.