I work for a software company that develops productivity applications for financial professionals (bankers, traders, portfolio managers, etc.). Our core activity is the distribution and presentation of numbers. Again and again over the years I have seen questions coming from clients, or from our client support staff, about the accuracy of numbers. Lay people (i.e. non software developers) understand the basic notion that computers store numbers to a limited degree of precision but their conceptual understanding stops there. If I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard someone say (or more accurately, write) that “floating point” numbers (they know the term at least) are accurate to only seven significant figures, then I would be a rich man. It’s not that straight forward. I’ve tried, and failed, on several occasions to educate people as to how floating point representation actually works. However, despite that track record, I am going to try one more time.

Base

The first thing we need to understand is the concept of base in the representation of numbers. Actually, even before that we need to recognize that “123” is just a symbolic representation of the abstract concept of the number one hundred and twenty three. And (and this is the important part) it’s only one of a whole range of possible symbolic representations. “123” is the representation of the number in base 10 positional notation. Now that representational system happens to be a very natural and convenient one that is rooted in the history of western culture. In fact, it’s how we “say” numbers in English (and many other languages): “one hundred and twenty three”. Well, roughly speaking that is, one might argue that perhaps it should be “one hundred, two tens and three”, but we’re not here to talk about the history of the evolution of the English language; we’re here to talk about floating point, and first about base.

Let’s think about what a set of digits in base 10 positional notation actually means. It’s a description of a sum of multiples of powers of ten.

\[123_{base10} = (1 \times 10^2) + (2 \times 10^1) + (3 \times 10^0)\]More generally, for an integer N:

\[N_{base10} = \sum_{i=+\infty}^{0}{d_i10^i}\]Where \(d_i\) are the digits of N in base 10.

We can extend this beyond integers of course.

\[123.45_{base10} = (1 \times 10^2) + (2 \times 10^1) + (3 \times 10^0) + (4 \times 10^{-1}) + (5 \times 10^{-2})\]Or more generally, for a real number R:

\[R_{base10} = \sum_{i=+\infty}^{-\infty}{d_i10^i}\]Of course we don’t have to use base 10; any base will do. The representation of R in base B is:

\[R_{baseB} = \sum_{i=+\infty}^{-\infty}{d_iB^i}\]For example, using base 8:

\[123.45_{base10} = (1 \times 8^2) + (7 \times 8^1) + (3 \times 8^0) + (3 \times 8^{-1}) + (4 \times 8^{-2}) + (6 \times 8^{-3}) + (3 \times 8^{-4}) + (1 \times 8^{-5}) + ...\] \[123.45_{base10} = 173.34631..._{base8}\]Note the use of the ellipsis there to indicate that the digits continue. They continue forever actually with the four digit pattern \(4631\) repeating again and again. The thing to note here is that a fraction with a relatively compact representation in one base (\(.45_{base10}\)) can have a much more verbose representation in another base. And the reverse can be true too.

\[0.001953125_{base10} = (1 \times 8^{-3}) = 0.001_{base8}\]The fractional part of the base N positional notation representation for a rational number will either terminate or fall into a repeating sequence of a fixed number of digits. Whether it’s one or the other will depend on the base. An irrational number, however, will have a non-terminating, non-repeating fractional part (e.g. \(\pi = 3.14159265 …\)).

Consider \(1 \over 10\). This is \(0.1\) in base 10 but \(0.000110011001100…\) in base 2, where the pattern of repeated digits (bits in this case) is \(0011\). And \(1 \over 3\) is \(0.1\) in base 3 but is \(0.3333333…\) in base 10 with \(3\) repeated forever.

Scientific Notation

The second thing we need to understand is the concept of scientific notation, a standard way of writing numbers that are too big or too small to be conveniently written in decimal form. In this notation any Real number R is represented as:

\[R = m \times B^e\]Where m is the normalized value of R (called the significand or mantissa) and e is an integer (called the exponent). m is chosen such that \(B^0 \leq |m| < B^1\) and e is chosen accordingly. For example:

\[123.456_{base10} = 1.23456 \times 10^2\] \[0.00123456_{base10} = 1.23456 \times 10^{-3}\]Significant Figures

The final thing we need to understand is that for obvious reasons we can’t store and manipulate numbers in a representation that requires an infinite number of digits. We are always going to have to limit the amount of space (computer memory or literal space on a page) required, and trade precision for storage size. So, we have the concept of the maximum number of contiguous digits (known as the number of significant figures) that can be part of a given representation.

Let’s look at a base 10 example using scientific notation and assume that we use a fixed 6 significant figures for the mantissa and 2 for the exponent.

\[123.456789012_{base10} = 1.23457 \times 10^{02}\] \[123,456,789,012_{base10} = 1.23457 \times 10^{11}\] \[0.000000000123456789012_{base10} = 1.23457 \times 10^{-10}\]In the first case we actually store \(123.457\) which is off by \(0.000210988\); in the second case we actually store \(123,457,000,000\) which is off by \(210,988\); and in the third case we actually store \(0.000000000123457\) which is off by \(0.000000000000000210988\). In all cases the delta in percent terms is the same: \(0.000171\%\).

Floating Point

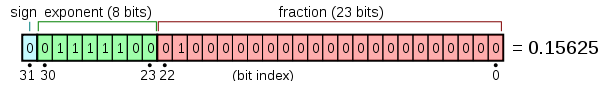

And so finally we come to floating point representation as codified in the IEEE 754 standard, Commonly encountered formats are 32 bit (“single precision” or “float”) and 64 bit (“double precision” or “double”). Both use the same structure to represent a number in base 2 scientific notation but allocate a different number of bits to each part. A single precision value is structured like this:

There’s an initial sign bit, followed by 8 bits in which the exponent value (e) is stored as an unsigned integer (with a bias of 127), followed by 23 bits in which the digits of the normalized mantissa are represented with an implicit leading 1 digit (i.e. \(1.b_{22}b_{21}b_{20}…b_0\)). The represented value is given by:

\[value = (-1)^{s} \times (1 + m) \times 2^e\]where \( e = e_{biased} - 127 \), \( e_{biased} = \sum_{i=23}^{30}{b_i2^{i-23}} \) and \(m = \sum_{i=22}^{0}{b_i}2^{i-23}\).

In the above example:

\[sign = 0\] \[m = \sum_{i=22}^{0}{b_i2^{i-23}} = 2^{-2} = 0.25\] \[e_{biased} = \sum_{i=23}^{30}{b_i2^{i-23}} = 2^2 + 2^3 + 2^4 + 2^5 + 2^6 = 124\] \[e = -3\] \[2^e = 2^{-3}\] \[value = (-1)^0 \times (1 + 0.25) \times 2^{-3} = 0.15625\]Double precision values use 11 bits to store the exponent and 52 bits to store the mantissa.

So, what about the misconception that we mentioned at the top of this post, that a float is accurate to 7 significant figures? Well, I hope you now realize that it depends on the number and how that number can be represented as a sum of powers of 2. The number \(1 \over 65536\) is \(0.0000152587890625\) in base 10 but that can be represented with 100% accuracy in a float since it’s just \(1 \times 2^{-16}\). However the number \(1 \over 10\), \(0.1\) in base 10, cannot be represented accurately in a float since it cannot be represented as a finite sum of powers of 2.

\[0.1 = 2^{-4} + 2^{-5} + 2^{-8} + 2^{-9} + 2^{-12} + 2^{-13} + 2^{-16} + 2^{-17} + ...\]With only 24 significant binary digits the infinite summation terminates and is equal to \(3355443 \over 33554432\) which is \(0.0999999940395355\).

So, the next time someone says that a float has 7 significant figures, the correct answer is “well, that depends …”.