If I have a function, f, defined as …

\[f(x) = x^x\]Then what is its derivative \(f'(x)\)?

Well, the answer is \(f'(x) = x^x(1 + ln(x))\) but how would we figure that out?

Tools

How to start here? None of our basic rules for derivatives apply. This isn’t a polynomial; it doesn’t involve triganometric functions; it’s not a traditional exponential with a constant base; it doesn’t involve logarithms.

Well, the answer does involve logarithms and we’ll soon see why. Logatithms invariably show up when deadling with exponential things. What other tools are in our toolbox for calculating derivatives? The product and quotient rules, the chain rule, etc. Do these help? They do actually and we can see how by introducing some other functions.

Approach #1

As an aside, let’s consider two new functions, g and h …

\[g(x) = ln(x)\] \[h(x) = g(f(x))\]We know the derivative of the natural logarithm function and we can apply the chain rule to calculate the derivative of the composition of two functions. So …

\[g'(x) = \frac{1}{x}\] \[h'(x) = g'(f(x))f'(x)\]Combining the two we get …

\[h'(x) = \frac{f'(x)}{f(x)} = \frac{f'(x)}{x^x}\]We also know, from its definition, that …

\[h(x) = ln(x^x)\]And we can apply one of the rules of logarithms to rewrite this as …

\[h(x) = xln(x)\]Now we can apply the product rule for derivatives, namely, that if \(c(x) = a(x)b(x)\) then …

\[c'(x) = a'(x)b(x) + a(x)b'(x)\]To calculate \(h'(x)\) as the following, using \(a(x) = x\) and \(b(x) = ln(x)\), …

\[h'(x) = 1\cdot{ln(x)} + x\cdot{\frac{1}{x}}\]Which simplifies to …

\[h'(x) = ln(x) + 1\]Now let’s put things together. We have …

\[h'(x) = 1 + ln(x)\]And

\[h'(x) = \frac{f'(x)}{x^x}\]And so …

\[\frac{f'(x)}{x^x} = 1 + ln(x)\]And finally …

\[f'(x) = x^x(1 + ln(x))\]QED

Approach #2

Let’s rewrite \(f(x)\) as …

\[f(x) = e^{ln(x^x)} = e^{xln(x)}\]Now we can apply the chain rule directly with \(f(x) = g(h(x))\), \(g(x) = e^x\) and \(h(x) = xln(x)\) to get …

\[f'(x) = g'(h(x))h'(x)\] \[g'(x) = e^x\]And via the product rule …

\[h'(x) = 1 + ln(x)\]So …

\[f'(x) = e^{xln(x)}(1 + ln(x)) = x^x(1 + ln(x))\]QED

Comments on the function

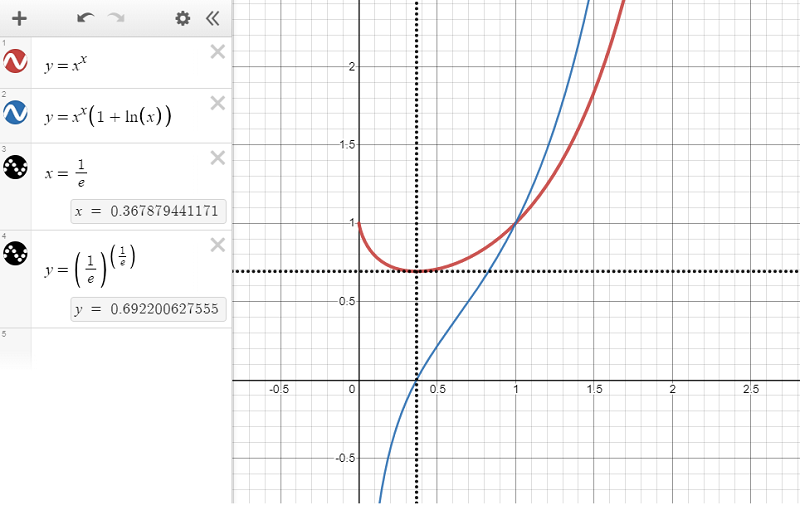

The function \(f(x) = x^x\) is an interesting one. If we think of it as a function from the real numbers to the real numbers then it’s domain obviously includes \(x \in (0, \infty)\). For all such real values it has a real value. Clearly \(\lim_{x\to\infty} f(x) = \infty\) and its minimum value is where \(f'(x) = 0\), i.e. where \(x^x(1 + ln(x)) = 0\), \(ln(x) = -1\), \(x = \frac{1}{e}\). At this value of \(x\), \(f(x) = (\frac{1}{e})^{\frac{1}{e}} \approx 0.6922\). For \(x \in (0, \frac{1}{e})\) \(f'(x)\) is negative and so the value of \(f(x)\) is decreasing.

So \(f(x)\) decreases as \(x\) increases over \(x \in (0, \frac{1}{e})\) to a minimum value of \((\frac{1}{e})^{\frac{1}{e}}\) for \(x = \frac{1}{e}\), and then increases as x increases over \(x \in (\frac{1}{e}, \infty)\).

But what about \(x = 0\)? What is the value of \(0^0\)? Or more precisely what is \(\lim_{x \to 0+} x^x\)?

This is the same as asking what is \(\lim_{x \to 0+} e^{xln(x)}\)?

Because \(e^x\) is such a well behaved continuous function we can say that …

\[\lim_{x \to 0+} e^{xln(x)} = e^{ \lim_{x \to 0+} xln(x) }\]So let’s focus on the limit in the exponent now, i.e. \(\lim_{x \to 0+} xln(x)\). We can rewrite this as …

\[\lim_{x \to 0+} xln(x) = \lim_{x \to 0+} \frac{ln(x)}{\frac{1}{x}}\]Now, recall L’Hôpital’s rule that states that for sufficiently well behaved functions \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\) …

\[\lim_{x \to 0+} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim_{x \to 0+} \frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}\]We can apply this to our limit above and differentiate the numerator and denominator to see that …

\[\lim_{x \to 0+} \frac{ln(x)}{\frac{1}{x}} = \lim_{x \to 0+} \frac{\frac{1}{x}}{\frac{-1}{x^2}} = \lim_{x \to 0+} -x = 0\]So …

\[\lim_{x \to 0+} x^x = \lim_{x \to 0+} e^{xln(x)} = e^{ \lim_{x \to 0+} xln(x) } = e^0 = 1\]And finally we can extended the domain of our function to include \(x = 0\) and say that \(f(0) = 1\).

This is summarized in the chart from the top of this post, shown again below …

Now It All Gets a Bit Complex …

But what about values of \(x^x\) for \(x\) less than \(0\)? For the negative integers the function’s value is still real …

\[\frac{1}{(-1)^1}, \frac{1}{(-2)^2}, \frac{1}{(-3)^3}, \frac{1}{(-4)^4}, \frac{1}{(-5)^5}, ...\]I.e.

\[-1, \frac{1}{4}, -\frac{1}{27}, \frac{1}{256}, -\frac{1}{3125}, ...\]Or more generally, for \(n \in [1, \infty)\) …

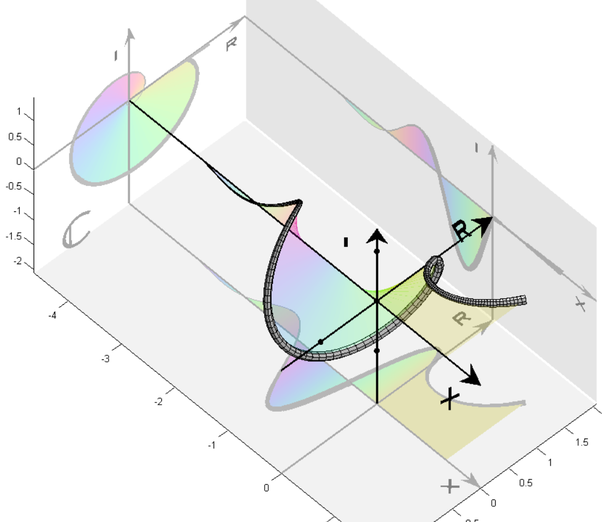

\[(-1)^n\frac{1}{n^n}\]But what about for non-integer negative values of \(x\)? Here the function is not defined over the real numbers but it is defined over the complex numbers. When we step into the complex plane we see a beautiful continuous spiral appear with the complex value of \(x^x\) rotating clockwise around the negative real axis for increasing negative real values of \(x\). The top and bottom points on this spiral correspond to a zero imaginary component and the real values that we saw above for negative integer values of \(x\).

The following chart illustrates this …

Quite beautiful.