The Claim

I saw this interesting math nugget on the Internetz recently …

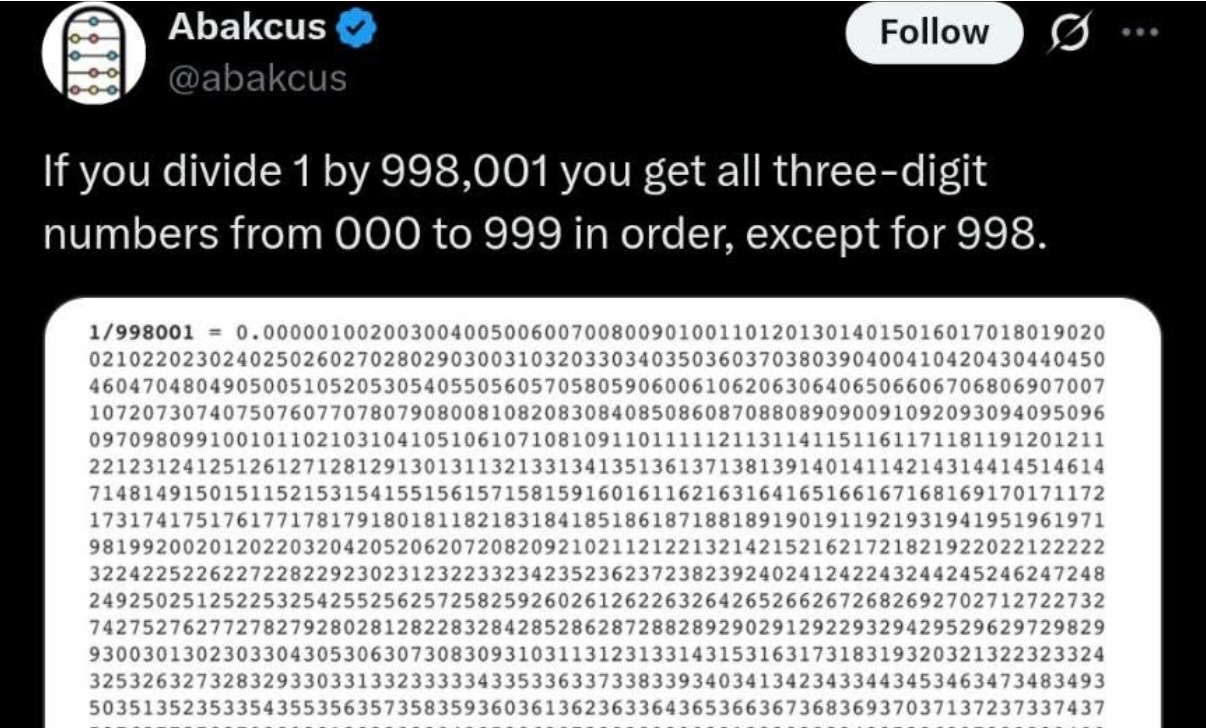

“If you write 1 / 998,001 as a decimal then you get all the numbers from 000 to 999 in order except for 998”

… and I said to myself “Really? Why’s that then?”

So here we are again. Let’s think about this.

Thinking

1 / 998,001 is actually \(\frac{1}{999^2}\) which is also \(\frac{1}{(1000 - 1)^2}\)

For now, let’s just think about \(\frac{1}{999}\). We can rewrite this as …

\[\frac{1}{999} = \frac{1}{1000 - 1} = \frac{1}{1000}\cdot\frac{1000}{1000 - 1} = \frac{1}{1000}\cdot\frac{1}{1 - \frac{1}{1000}}\]Now, let’s recall the following about geometric series …

\[\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} r^n = \frac{1}{1 - r}, \qquad \lvert r \rvert < 1\]Well, \(\frac{1}{1000}\) is certainly less than one, so we can apply this formula to the above, to get …

\[\frac{1}{999} = \frac{1}{1000}\cdot\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{1}{1000^n} = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{1000^n}\]But what happens when we square it? For now let’s consider this …

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{(x - 1)^2} &= (\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{x^n})^2 = (\frac{1}{x^1} + \frac{1}{x^2} + \frac{1}{x^3} + \dots) (\frac{1}{x^1} + \frac{1}{x^2} + \frac{1}{x^3} + \dots) \\ &= \frac{1}{x^1}(\frac{1}{x^1} + \frac{1}{x^2} + \frac{1}{x^3} + \dots) + \frac{1}{x^2}(\frac{1}{x^1} + \frac{1}{x^2} + \frac{1}{x^3} + \dots) + \frac{1}{x^3}(\frac{1}{x^1} + \frac{1}{x^2} + \frac{1}{x^3} + \dots) + \dots \\ &= \frac{1}{x^2} + \frac{2}{x^3} + \frac{3}{x^4} + \frac{4}{x^5} + \dots \\ &= \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{n}{x^{n + 1}} \end{aligned}\]And with \(x = 1000\) we get …

\[\frac{1}{999^2} = (\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{1000^n})^2 = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{n}{1000^{n + 1}}\]If we write the infinite sum as a decimal then we get …

\[\begin{align*} \frac{1}{999^2} &=\phantom{+} 0.000\,001\\ &\phantom{=}+ 0.000\,000\,002\\ &\phantom{=}+ 0.000\,000\,000\,003\\ &\phantom{=}+ 0.000\,000\,000\,000\,004\\ &\phantom{=}+ \dots\\ &\phantom{=}+ 0.000\,000\,000\,000\,000\,\dots\,997\,000\,000\,000\,\dots\\ &\phantom{=}+ 0.000\,000\,000\,000\,000\,\dots\,000\,998\,000\,000\,\dots\\ &\phantom{=}+ 0.000\,000\,000\,000\,000\,\dots\,000\,000\,999\,000\,\dots\\ &\phantom{=}+ 0.000\,000\,000\,000\,000\,\dots\,000\,000\,001\,000\,\dots\\ &\phantom{=}+ \dots \end{align*}\]When we get to the term \(\frac{1000}{1000^{1001}}\) we see that the leading digit of the numerator (\(1000\)) will overlap with the last digit of \(999\). This will result in the \(999\) flipping to \(1000\), and then that will result in the \(998\) flipping to \(999\). There will be no more overlapping digits downstream from there though.

This pattern will repeat again and again. The final result will be …

\[\frac{1}{999^2} = \frac{1}{998001} = 0.\overline{000\,001\,002\,003\,\dots\,997\,999}\]More generically

We can easily see that the same pattern would work for \(\frac{1}{(10^n - 1)^2}\) for any \(n > 0\).

So, for example …

\[\frac{1}{99^2} = \frac{1}{9801} = 0.\overline{00\,01\,02\,03\,\dots\,97\,99}\]And …

\[\frac{1}{9^2} = \frac{1}{81} = 0.\overline{0\,1\,2\,3\,\dots\,7\,9}\]QED