A prime number is a positive integer (a natural number) that is only evenly divisible by itself and one. The number one itself, by convention, is not considered a prime. A natural number, greater than one, that is not prime is said to be composite.

Primes can be considered as the building blocks of all positive numbers. A statement that is more formally expressesd by the fundametal theorem of arithmetic which states that every natural number, greater than one, is either a prime or can be factorized as a product of primes that is unique except for their order.

Some interesting questions come to mind …

- How many primes are there?

- How common are primes?

- How do we determine whether a given number is prime?

- What is the billionth prime?

I already answered #1 in my post about proof. There are infinitely many.

The distribution of primes within the natural numbers can be statistically modelled. The prime number theorem formalizes the intuitive idea that primes become less common as they become larger and introduces the prime counting function, \(\pi(N)\), defined as the number of prime numbers less than or equal to N. The use of \(\pi\) as a function here is unrelated to the number \(\pi\).

The prime number theorem states that …

\[\pi(n) \sim \frac{n}{\log n}\]Or more formally …

\[\lim_{n\to\infty} \frac{\pi(n)}{\frac{n}{\log n}} = 1\]This means that for large enough N, the probability that a random integer not greater than N is prime is very close to \(\frac{1}{\log N}\).

How to determine that a given number, N, is prime

Such a test is known as a primality test.

A simple brute force algorithm would be to enumerate all of the natural numbers less than N and see whether any of them evenly divide N. If any of them do then N is composite, otherwise it is prime.

Actually, we only have to test potential divisors less than or equal to \(\sqrt N\). This is because if N is composite then at least one of its factors must be less than or equal to \(\sqrt N\). To justify this assume that N is composite and \(N = a \times b\). If both \(a\) and \(b\) were greater than \(\sqrt N\) then \(a \times b\) would be greater than N. This is clearly impossible and so at least one of the factors must be \(<= \sqrt N\).

Ideally we would enumerate only the prime numbers less than N but this presupposes that we know all such primes. We can limit the test divisors somewhat by noting that all primes > 3 can be written as \(6n - 1\) or \(6n + 1\) for \(n = 1, 2, ...\) so so we only have to enumerate test factors of that form.

To see why this is so note that we can enumerate all natural numbers (> 5) as …

\(6n, 6n + 1, 6n + 2, 6n + 3, 6n + 4, 6n + 5\) for \(n = 1, 2, 3, ...\)

The numbers of the form \(6n, 6n + 2\) and \(6n + 4\) are all divisible by 2 and therefore are not prime. The numbers of the form \(6n\) and \(6n + 3\) are all divisible by 3 and therefore are not prime either. This just leaves those of the form \(6n + 1\) and \(6n + 5\) as candidate primes. The \(6n+5\) numbers are equivalent to \(6n - 1\).

Here’s an initial implementation of the brute force primality test in C# …

namespace PrimeNumbers {

using System;

public static class NumberExtentions {

public static bool IsPrime(this ulong number)

{

if(number < 2) return false; // 0 & 1 are not prime

if(number < 4) return true; // 2 & 3 are prime

if(number % 2 == 0) return false; // 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, ... are composite

if(number % 3 == 0) return false; // 9, 15, 21, 27, 33, ... are composite

// Now test for factors of the form 6n - 1 and 6n + 1 for n = 1, 2, 3, ...

// 6n - 1 : 5, 11, 17, 23, 29, ...

// 6n + 1 : 7, 13, 19, 25, 31, ...

// ... up through floor(sqrt(number))

var max = (ulong)Math.Sqrt(number);

// We will get here for number = 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 25, 29, 31, 35, ...

// Those numbers with floor(sqrt(number)) < 5 will not go through this loop at all

// That's OK though since all of those numbers are prime: 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23

// 6n - 1 and 6n + 1 for n = 1, 2, 3, ...

// is equivalent to n and n + 2 for n = 6m + 5 where m = 0, 1, 2, ...

for(ulong n = 5; n <= max; n += 6) {

if(number % n == 0) return false;

if(number % (n + 2) == 0) return false;

}

return true;

}

}

}

We can also leverage known primes. If N is small then we can simply do a lookup into a list of all known primes up to some value.

There are also probabilistic methods for testing primality, e.g. the Miller-Rabin test. This sort of method takes the number to be tested along with a factor indicating the required accuracy. Methods like this are efficient and useful when testing very large numbers for primality but for moderately sized numbers their performance lags significantly behind the exhaustive test methods.

The nth Prime

Being able to test a given number for primality is one thing but enumerating the primes in sequence is something else. In order to determine what is the billionth prime we need to generate, and count, prime numbers from 2 up to one billion. What’s an efficient way to do this?

Well, let’s start with brute force and then try to optimize from there. We’ll start by looking for the millionth prime, a little less ambitious than the billionth to start with.

Method 1

Loop over all the natural numbers, test each for primality using the above IsPrime function, count the primes and stop when we get to the millionth one. Do this all in a single thread.

Results …

With JIT compiler optimized C# code running on my 2017 MacBook Pro Core i7 @ 2.9GHz this takes, on average, 7.17 seconds to complete and then reports that the millionth prime is \(15,485,863\). According to the Interwebz that is the correct answer.

We can do better. We don’t need to test every natural number for primality. As in the IsPrime test function we can iterate over the superset of the primes defined by \(6n-1\) and \(6n+1\).

Method 2

As method 1 but looping over the smaller set of candidate primes.

Results …

A tiny bit better. Runtime is now 7.03 seconds on average. No significant improvement though.

We need a different approach.

The Sieve of Eratosthenes

We will look to a polymath from antiquity for inspiration, a man named Eratosthenes of Cyrene. He was a Greek mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer and music theorist who ultimately become the chief librarian of the Library at Alexandria. He is credited with the invention of a simple simple algorithm for finding all the prime numbers up to any given limit. This algorithm is now known as the Sieve of Eratosthenes.

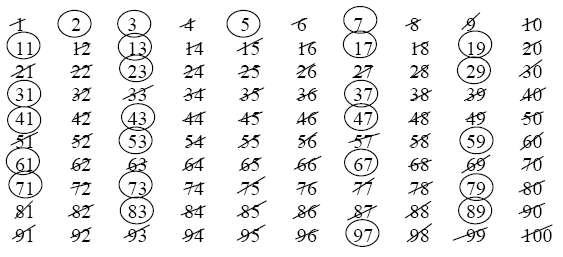

The algorithm iteratively marks as composite the multiples of each number up to a given limit.

Example: To Find All the Primes Less Than or Equal to 30

First list all the natural numbers from 2 to 30 …

\[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30\]The first number in the list is \(2\). Go through the list and cross out all the multiples of \(2\) other than \(2\) itself..

\[2, 3, \color{red}{4}, 5, \color{red}{6}, 7, \color{red}{8}, 9, \color{red}{10}, 11, \color{red}{12}, 13, \color{red}{14}, 15, \color{red}{16}, 17, \color{red}{18}, 19, \color{red}{20}, 21, \color{red}{22}, 23, \color{red}{24}, 25, \color{red}{26}, 27, \color{red}{28}, 29, \color{red}{30}\]The next uncrossed number in the list is \(3\). Go through the list and cross out all the multiples of \(3\) other than \(3\) itself …

\[2, 3, \color{lightgrey}{4}, 5, \color{lightgrey}{6}, 7, \color{lightgrey}{8}, \color{red}{9}, \color{lightgrey}{10}, 11, \color{lightgrey}{12}, 13, \color{lightgrey}{14}, \color{red}{15}, \color{lightgrey}{16}, 17, \color{lightgrey}{18}, 19, \color{lightgrey}{20}, \color{red}{21}, \color{lightgrey}{22}, 23, \color{lightgrey}{24}, 25, \color{lightgrey}{26}, \color{red}{27}, \color{lightgrey}{28}, 29, \color{lightgrey}{30}\]The next uncrossed number in the list is \(5\). Go through the list and cross out all the multiples of \(5\) other than \(5\) itself …

\[2, 3, \color{lightgrey}{4}, 5, \color{lightgrey}{6}, 7, \color{lightgrey}{8}, \color{lightgrey}{9}, \color{lightgrey}{10}, 11, \color{lightgrey}{12}, 13, \color{lightgrey}{14}, \color{lightgrey}{15}, \color{lightgrey}{16}, 17, \color{lightgrey}{18}, 19, \color{lightgrey}{20}, \color{lightgrey}{21}, \color{lightgrey}{22}, 23, \color{lightgrey}{24}, \color{red}{25}, \color{lightgrey}{26}, \color{lightgrey}{27}, \color{lightgrey}{28}, 29, \color{lightgrey}{30}\]The next uncrossed number in the list is \(7\). Multiples of \(7\) will result in no more exclusions since all such numbers have already been crossed out. We should note that this will be the case as soon as the first uncrossed out number in a given pass through the array is greater than \(\sqrt{N}\) where N is the size of the array, \(30\) in our example.

Note that all the even numbers will be crossed out as we walk through the array eliminating multiples of \(2\) so there’s really no point writing them down in the first place. We can just write down the odd numbers and save half the space. Of course we have to remember that there is one even prime though, namely \(2\).

Another thing to note is that for each starting number, \(n\), all the multiples of that number less than the square of \(n\) will have already been crossed out, so we can start crossing out multiples of \(n\) from \(n^2\).

At this point we are done. All of the remaining uncrossed numbers are the primes.

We can write an implementation of this algorithm in C# …

namespace PrimeNumbers {

using System;

public static class Numbers {

public static IEnumerable<uint> PrimesLessThan(uint maxNumber)

{

if(maxNumber < 3) yield break;

// Allocate an array of flags

// We don't need to consider even numbers so we only need maxNumber / 2

var numberIsComposite = new bool[maxNumber / 2];

yield return 2; // 2 is the only even prime, output that one by default

// For odd n, 3 -> sqrt max, output primes and mark all prime multiples (from n^2) as composite

uint n = 3;

var sqrtMaxNumber = (uint)System.Math.Sqrt(maxNumber);

for(; n <= sqrtMaxNumber; n += 2) {

if(numberIsComposite[n / 2]) continue;

yield return n;

for(ulong m = n * n; m < maxNumber; m += 2 * n) // m is ulong to avoid overflow

numberIsComposite[m / 2] = true;

}

// Continue to walk through the rest of the array and output each prime number

for(; n < maxNumber; n += 2)

if(!numberIsComposite[n / 2]) yield return n;

}

}

}

This will generate each prime up to and including maxNumber.

We can use this algorithm to find the millionth prime. The only tricky part is that we need to pass in a value for the largest number to consider. In other words we need to come up with an estimate for how big the millionth prime will be. We will address this limitation in due course but for now let’s just get a rough benchmark on the performance of this strategy.

Method 3

Use the Sieve of Eratosthenes with an upper bound of \(15,500,000\) for the internal array of numbers. Count the resulting primes and output the millionth one. Here’s the code …

namespace ScratchConsoleApp

{

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using PrimeNumbers;

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

const uint maxNumber = 15500000; // Magically chosen max value ...

uint count = 0;

uint nthPrime = 0;

var sw = new Stopwatch();

sw.Start();

foreach(var prime in Numbers.PrimesLessThan(maxNumber)) {

++count;

if(count == n) nthPrime = prime;

}

sw.Stop();

Console.WriteLine($"The {n}th prime is {nthPrime}");

Console.WriteLine($"Elapsed = {sw.Elapsed}");

}

}

}

Results …

With JIT compiler optimized C# code running on my 2017 MacBook Pro Core i7 @ 2.9GHz this takes, on average, 0.13 seconds to complete and then reports that the millionth prime is \(15,485,863\), which we know to be correct.

Wow! That’s much faster than before.

This implementation has additional scope for improvement as well.

- Support finding primes larger than uint.MaxValue

- Create a simpler interface to allow us to request the Nth prime and remove the need to specify an upper bound for the value of the prime

- Chunking, to achieve better locality of memory access (to improve CPU L1 and L2 cache hit rates)

- Use threads to leverage multiple CPU cores in parallel

There are some simple tweaks too. It turns out that the IEnumerable interface and the yield return construct have some overhead. If we change the code to …

namespace PrimeNumbers {

using System;

public static class Numbers {

public static void ForEachPrimeLessThan(uint maxNumber, Action<uint> primeFn)

{

if(maxNumber < 3) return;

// Allocate an array of flags

// We don't need to consider even numbers so we only need maxNumber / 2

var numberIsComposite = new bool[maxNumber / 2];

primeFn(2); // 2 is the only even prime, output that one by default

// For odd n, 3 -> sqrt max, output primes and mark all prime multiples (from n^2) as composite

uint n = 3;

var sqrtMaxNumber = (uint)System.Math.Sqrt(maxNumber);

for(; n <= sqrtMaxNumber; n += 2) {

if(numberIsComposite[n / 2]) continue;

primeFn(n);

for(ulong m = n * n; m < maxNumber; m += 2 * n) // m is ulong to avoid overflow

numberIsComposite[m / 2] = true;

}

// Continue to walk through the rest of the array and output each prime number

for(; n < maxNumber; n += 2)

if(!numberIsComposite[n / 2]) primeFn(n);

}

}

… and use it like this …

namespace ScratchConsoleApp

{

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using PrimeNumbers;

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

const uint maxNumber = 15_500_000; // Magically chosen max value ...

uint count = 0;

uint nthPrime = 0;

var sw = new Stopwatch();

sw.Start();

Numbers.ForEachPrimeLessThan(maxNumber, prime => {

++count;

if(count == n) nthPrime = prime;

});

sw.Stop();

Console.WriteLine($"The {n}th prime is {nthPrime}");

Console.WriteLine($"Elapsed = {sw.Elapsed}");

}

}

}

… then the results are slightly better.

A Better Sieve

Let’s make our sieve implementation better. First we want to support finding larger primes which means that we need to use 64 bit integers (ulong) as opposed to 32 bit (uint). For the smaller primes this will be a waste of space but we will need the extra capacity in order to work with primes up to and including the billionth one.

Our existing sieve implementation uses a single working array of bool where the index of each element corresponds to a number that we want to test for primality. This means that the maximum number that we can test is the array size less one. Now, the .Net Framework imposes a limit of Int32.MaxValue (\(2^{31}-1\)) on the number of elements in an array and therefore also imposes a limit on the size of the maximum prime that we can find. We optimize our use of the working array by ignoring even numbers (> 2) and associating index \(n\) with the number \(2n + 1\) but this still caps us out at 4 billion or so. To test larger numbers we will need a different approach.

Sieving in Blocks

We can search for primes in blocks and reuse our working array for each block. Let’s look at an example of how this will work. Say we want to limit the size of our working array to 30 elements but we want to find all the primes up to 300.

Recall that we only ever need to eliminate multiples of primes from our working array where the primes are less than or equal to the square root of the largest number in the array. Now, floor(sqrt(300)) = 17 and so first we need to find all the primes up to 17. To do this we need a working array with 9 elements. We assume that we have a working array with 30 elements so we have enough for this first task.

Array index (n): 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ... 29

Corresponding number (2n + 1): 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 ... 59

We run the basic sieve (as before) on this working array to generate the primes: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13 & 17.

Now with this list of primes saved we will proceed to examine the numbers up to 300 in blocks of 60 (2 * working array size). Here’s the first block …

block #1

startNumber (s) = 0

n: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29

s+2n+1: 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47 49 51 53 55 57 59

We eliminate all multiples of the primes that we determined before. For each prime \(p\) we eliminate \(p^2 + 2kp\) for \(k = 0, 1, 2, ...\) until we pass the end of the block.

block #1

startNumber (s) = 0

n: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29

s+2n+1: 1 3 5 7 11 13 17 19 23 29 31 37 41 43 47 53 57

Now the next block …

block #2

startNumber (s) = 60

n: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 ... 29

s+2n+1: 61 63 65 67 69 71 73 75 77 79 81 83 85 87 89 91 93 95 97 99 101 103 105 107 109 111 ... 119

… which becomes the following after eliminating multiples of our primes …

block #2

startNumber (s) = 60

n: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 ... 29

s+2n+1: 61 67 71 73 79 83 89 97 101 103 107 109 ...

Let’s look at a later block …

block #5

startNumber (s) = 240

n: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 ... 29

s+2n+1: 241 243 245 247 249 251 253 255 257 259 261 263 265 267 269 271 273 275 277 279 281 ... 299

Here the first number in the block is 241. As we enumerate our primes we end up skipping over many multiples of them before we get to a number that is in the block.

p p^2 +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p +2p ...

3 9 15 21 27 33 39 45 51 57 63 69 75 81 87 93 99 105 111 117 123 129 135 141 ...

5 25 35 45 55 65 75 85 95 105 115 125 135 145 155 165 175 185 195 205 215 225 235 245 ...

7 49 63 77 91 105 119 133 147 161 175 189 203 217 231 245 259 273 287 301 ...

11 121 143 165 187 209 231 253 275 297 319 ...

13 169 195 221 247 273 299 ...

17 289 ...

Rather than having to iterate over all of these redundant prime multiples we can skip ahead with some appropriate arithmetic (see below).

Here’s some C# code to sieve a block …

private static void SieveBlock(bool[] isPrime,

IReadOnlyList<ulong> primes,

uint startIndex,

ulong startNumber,

ulong endNumber)

{

foreach(var p in primes) {

if(p == 2) continue; // 2 is a special case not covered by our working array

// Start eliminating elements of the working array from p^2

var n = p * p;

if(n > endNumber) break;

// In the for loop below, n = p*p + 2*k*p for +ve integers k = 0, 1, 2, ...

// We don't need to do anything until n is >= startNum so fast forward until that is true

if(n < startNumber) {

// Find the smallest k such that n + 2*k*p >= startNum

// k >= (startNum - n) / (2 * p)

// k >= a / b for a = startNum - n and b = 2 * p

// k = a / b if a % b == 0 otherwise k = (a / b) + 1

var a = startNumber - n;

var b = 2 * p;

var k = a % b == 0 ? a / b : (a / b) + 1;

n = n + (2 * k * p);

}

// Mark all multiples of this prime as composite in the current range of the working array

for(; n < endNumber; n += 2 * p) {

var index = startIndex + (n - startNumber) / 2;

isPrime[index] = false;

}

}

}

Using block processing like this we can come up with a sieve that will work for much larger numbers.

Method 4

Use a block processing Sieve of Eratosthenes with a block size of 500,000 and an upper bound of 15,500,000. Count the resulting primes and output the millionth one.

Results …

c:\src\eratosthenes\BlockSieve.exe -blockSize=500000 -maxNumber=15500000 -nthPrime=1000000

The 1,000,000th prime is 15,485,863

Elapsed = 00:00:00.0622126

What about the 100 millionth prime? Well, our implementation can do that now.

Results …

c:\src\eratosthenes\BlockSieve.exe -blockSize=500000 -maxNumber=2100000000 -nthPrime=100000000

The 100,000,000th prime is 2,038,074,743

Elapsed = 00:00:09.6867032

What about the 500 millionth prime?

Results …

c:\src\eratosthenes\BlockSieve.exe -blockSize=500000 -maxNumber=11100000000 -nthPrime=500000000

The 500,000,000th prime is 11,037,271,757

Elapsed = 00:00:57.2004362

But what about that billionth prime?

Results …

c:\src\eratosthenes\BlockSieve.exe -blockSize=500000 -maxNumber=23000000000 -nthPrime=1000000000

The 1,000,000,000th prime is 22,801,763,489

Elapsed = 00:02:05.9492586

According to the Interwebz that is indeed the correct answer for the billionth prime.

But wait, we’re not done …

Parallel Block Processing

Once we have determined our intial list of primes then we can eliminate composite numbers from blocks in parallel.

private static void ParallelSieveBlocks(ulong endNumber,

uint blockSize,

Func<ulong, bool> primeFn,

bool[] isPrime,

IReadOnlyList<ulong> primes,

uint numTasks,

ulong startNum)

{

var tasks = new List<Task>((int)numTasks);

for(uint m = 0; m < numTasks; ++m) {

// Init the start index of the section of the working array that this task will use and the

// bounds of the numbers that it will process

var taskStartIndex = m * blockSize;

var taskStartNum = startNum + (m * 2 * blockSize);

var taskEndNum = taskStartNum + (2 * blockSize);

if(taskStartNum >= endNumber) break; // Short circuit if there's no more work to

if(taskEndNum > endNumber) taskEndNum = endNumber; // Adjust endNum if we are the last block

tasks.Add(Task.Run(() => SieveBlock(isPrime, primes, taskStartIndex, taskStartNum, taskEndNum)));

}

Task.WaitAll(tasks.ToArray());

}

How many parallel tasks can we spawn though? There’s really no point in using more than the number of cores on the local system. Thus we will end up with a partially parallel but still somewhat serial algorithm.

public static void ParallelSieve(ulong endNumber,

Func<ulong, bool> primeFn,

uint blockSize = 600000,

uint numTasks = 0)

{

// Save the value of floor(sqrt(endNumber)) and use it as a cap on the initial set of primes

var sqrt = (ulong)Math.Sqrt(endNumber);

if(numTasks == 0) numTasks = (uint)Environment.ProcessorCount;

// We allocate a working array of bool with blockSize elements for each task

var arraySize = blockSize * numTasks;

// We will use this same array for the initial serial sieve to find the primes up to 'sqrt' so

// it needs to be at least big enough to hold all the numbers up to that value. Remember that

// we are only allocating half the values though (the / 2 optimization) so we need to account

// for that.

var serialSieveSize = (sqrt + 1) / 2;

if(arraySize < serialSieveSize) arraySize = (uint)serialSieveSize;

// Allocate and init the Working array. This will be reused by the tasks during each loop.

var isPrime = new bool[arraySize];

InitArray(isPrime, 0);

// Allocate enough space to store 'sqrt' primes

var primes = new List<ulong>((int)sqrt);

// First serially determine all the primes up to and including 'sqrt'

Sieve(isPrime, sqrt + 1, p => primes.Add(p));

// We will now proceed in parallel blocks of size 'blockSize'. Each block will be for a subset

// of the numbers up to endNumber.

// We have to process all the numbers up to endNumber. How many blocks is this? Don't forget

// remainders.

var numElements = endNumber / 2;

var numBlocks = (uint)(numElements % blockSize == 0 ?

numElements / blockSize :

(numElements / blockSize) + 1);

// We will process the blocks numTasks at a time. How many loops will we require? Don't

// forget remainders.

var numLoops = numBlocks % numTasks == 0 ? numBlocks / numTasks : (numBlocks / numTasks) + 1;

// Main loop

for(uint n = 0; n < numLoops; ++n) {

InitArray(isPrime, n); // Re-initialize the array for reuse

// Init the bounds of the numbers that this loop will be working with

var startNum = (ulong)n * 2 * blockSize * numTasks;

var endNum = startNum + (2 * blockSize * numTasks);

if(endNum > endNumber) endNum = endNumber;

// Launch tasks to process each block of the working array in parallel and wait for them to

// complete

ParallelSieveBlocks(endNumber, blockSize, isPrime, primes, numTasks, startNum);

// All tasks done, enumerate over the working array and output primes

if(n == 0) primeFn(2); // 2 is a special case

var totalBlockSize = numTasks * blockSize;

for(uint m = 0; m < totalBlockSize; ++m) {

if(!isPrime[m]) continue;

var prime = startNum + (2 * m) + 1;

if(primeFn(prime)) return; // Return if the client code indicates they are done

}

}

}

Method 5

Use a parallel block processing Sieve of Eratosthenes with a block size of 500,000 and various upper bounds, count the resulting primes and output the millionth, 100 millionth, 500 millionth and the billionth ones.

Results …

c:\src\eratosthenes\ParallelBlockSieve.exe -blockSize=500000 -maxNumber=15500000 -nthPrime=1000000

The 1,000,000th prime is 15,485,863

Elapsed = 00:00:00.0558394

c:\src\eratosthenes\ParallelBlockSieve.exe -blockSize=500000 -maxNumber=2100000000 -nthPrime=100000000

The 100,000,000th prime is 2,038,074,743

Elapsed = 00:00:07.4914955

c:\src\eratosthenes\ParallelBlockSieve.exe -blockSize=500000 -maxNumber=11100000000 -nthPrime=500000000

The 500,000,000th prime is 11,037,271,757

Elapsed = 00:00:41:1140395

c:\src\eratosthenes\ParallelBlockSieve.exe -blockSize=500000 -maxNumber=23000000000 -nthPrime=1000000000

The 1,000,000,000th prime is 22,801,763,489

Elapsed = 00:01:23.4179141

Not bad.

I experimented with different block sizes but ultimately found that results were best when the block size was chosen to ensure that each block of working array (in use by the threadpool thread running each task) was small enough that it would stay in L2/3 cache for a core. For larger blocks we may be able to do more work in parallel, and thus ultimately execute fewer loops, but we pay more in memory access latency than we gain in saved serial calculations.

Results Comparison

Here’s a summary of the runtimes of our different methods (All times are minutes, seconds and milliseconds).

| nth Prime | Sequential IsPrime | Sieve | Block Sieve | Parallel Block Sieve |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000,000 | 07:03.000 | 00:00.130 | 00:00.062 | 00:00.056 |

| 100,000,000 | n/a | n/a | 00:09.687 | 00:07.491 |

| 500,000,000 | n/a | n/a | 00:57.200 | 00:41.114 |

| 1,000,000,000 | n/a | n/a | 02:05.949 | 01:23.418 |