Number

Let’s start with a question … What is a number? It’s an innocuous little inquiry but one that has a lot of depth. The answer could be various things: A quantity of stuff, a measure of something, a metric ascribed to some property. At it’s most basic it could be considered to be a count of things, and that’s probably where we (humble members of species Homo sapiens) first got started with the concept. Gog wanted to communicate to Stig how many rocks he had and so held up a number of fingers (ever present conveniently indicative counting devices) to show him. Thus the concept of number could have pre-dated language.

Conceptualizing a count of things is a natural way to start thinking about numbers. This could start symbolically, by holding up three fingers to indicate three things, but grow into other symbolic representations of a count: a word or an inscribed symbol. Of course there could be various different sounds/symbols that become associated with a given number, each born from their own cultural context, but there is also something universal about what those symbols represent; an overarching three-ness that transcends use of the word three or the symbol 3; or indeed the words “trois” (French), “tres” (Spanish) and “drei” (German); or the symbols III (Roman Numerals), 三 (Kanji) or 11 (binary). Some cultures even use different words to count different types of things, e.g. in Japanese you would say “mittsu” (三つ) when just arbitrarily counting but “san’nin” (三人) to indicate three people. Complex stuff and all born of the different context within which different human groups evolved language and writing. At the end of the day though the concept of three is universal, at least mathematically so.

Number Systems, Base and a Bias for 10

Let’s take a moment to think about the symbolic representation of numbers though. Those of you reading this blog (if there ever are any readers of this blog …) are probably English speaking and educated in the modern Western tradition of the positional decimal numeral system using Arabic numerals to represent the digits 0 to 9. I’ve written about this before as part of some articles on floating point numbers.

That system is a very useful one that makes it somewhat easy to do arithmetical operations by hand. It includes concepts that were once radical and even heretical; such as using a separate symbol (0) to represent “nil”, “nothing”, “none”; and the corresponding idea of using place/position to indicate a count of a base number, in this case 10. It always amazes me to think that the concept of a symbol for “none” was considered un-holy and that its use could be outlawed by the church. That says so much about the nature of religion. Sigh.

Why base ten though? I guess because we humans, on the whole, have ten fingers. The word digit, used both to refer to a finger and also a symbol in a place within a number, lends some credence to this idea. Not all cultures used 10 though. The Babylonians, the first to utilize a positional number system, used base 60 and had symbols for the digits 0 to 59. Hah, I used the word digit there again, to refer to a symbol indicating one of a specific set of numbers in a place within a positional number system. Could I have used a different word? Not one as concise, that would communicate the concept I wanted. Oh the limitations of language.

The Babylonian’s choice of 60 lives on in some form in the modern world. It’s why we have 60 seconds in a minute, 60 seconds in an hour and 360 degrees in a circle. 60 is also a great number for commerce because it has a lot of factors. If you have 60 things then you can easily split them in to equal batches of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20 and 30. To some degree this is why 12 (a dozen) was often a popular number for many uses because - again - it has a lot of factors (2, 3, 4 and 6). 10 only has 2 and 5.

Anyway, I just want to point out that base ten isn’t special, it just turned out to be popular enough to ultimately become a de-facto standard for the modern world.

Other Types of Number

So far we’ve only thought about numbers for counting whole things (0, 1, 2, 3, …). Such numbers are generally referred to as the Natural Numbers. Over time we humans (and mathematicians) have innovated and extended the concept of number in other directions, to usefully describe and work with other concepts.

Negative numbers were invented to track the idea of magnitude along with a binary direction (e.g. credit or debit in ledgers and banking). Numbers born of debt one could say. These numbers were subsequently codified as the Integers.

In order to deal with pieces of a whole (half, a third, etc.) and proportions, humans came up with fractions, later codified as the Rational Numbers, and rather than deal directly with fractions we extended the idea of the positional decimal numeral system via the introduction of the “decimal point” and the use of digits to the right of it to indicate quantities of 1/10, 1/100, 1/1000, etc. that were to be included in the implicit overall aggregate value that the chain of symbols represented (E.g. 25.5 to indicate twenty five and a half).

Next up we have numbers born more from mathematical exploration as opposed to common utility. Firstly we have the Irrational Numbers. It was the Greeks who first had a run in with these fellas when they considered the length of the hypotenuse of a unit right triangle, the quantity otherwise known as \(\sqrt{2}\). Such a number cannot be written as a fraction and so is not a rational number. For a neat proof of this see here. Thus it was discovered that there are numbers beyond the rationals and lo the irrationals were born.

Then we have the Real Numbers, the Algebraic Numbers, the Trancendental Numbers and the Complex Numbers. I’m not going to go into any real detail on these but they are all very important little beasties.

For now I want to focus back on decimal numbers and certain decimal representations in particular.

Special Decimal Numbers

\(\pi\) is probably the first “special” number that we meet during our mathematical education and very quickly we learn that it has an infinite decimal representation …

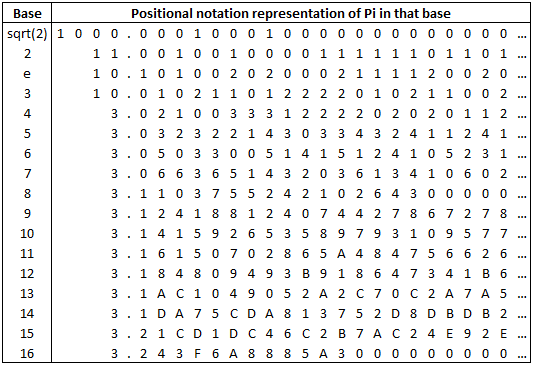

\[3.1415926535897932384626433862 ...\]Perhaps you tried to memorize the first N digits of \(\pi\) once. Then perhaps you had a life and you didn’t. Either way it’s definitely true that we humans have imbued these digits with some significance. Why though? They are not fundamentally special and instead are tied inextricably to the choice of base and the decimal positional number system. We could write \(\pi\) using various bases as I discussed here. It’s worth reminding ourselves of this …

The choice of base is arbitrary and the sequence of digits is equally arbitrary.

However, there does exist a more fundamental infinite representation of \(\pi\) but before we can talk about it we have to understand continued fractions.

Continued Fractions

A Continued Fraction is an expression obtained via an iterative process of representing a number as the sum of its integer part and the reciprocal of another number. Well, that’s the technical definition. Let’s start with a few examples and think about rectangles. Hey, geometry!

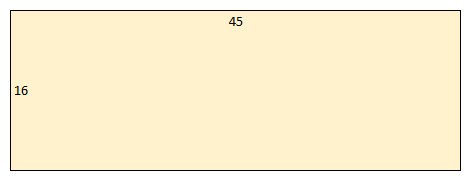

The continued fraction for a natural number is, trivially, just the natural number. Let’s consider the rational number \(\frac{45}{16}\) and think of the numerator and denominator as the lengths of the sides of a rectangle.

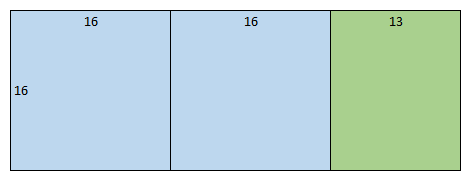

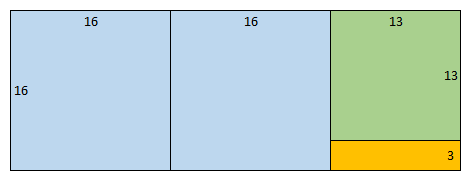

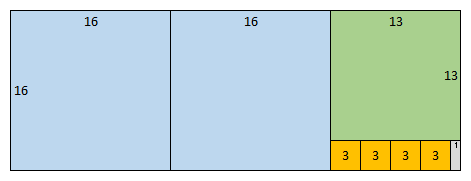

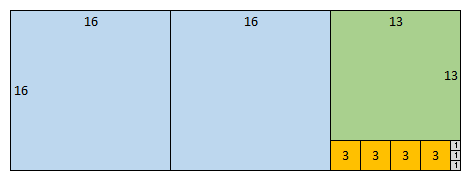

Now lets try to decompose this rectangle into squares. We can think of it as being composed of two squares (of side \(16\)) and another smaller rectangle (with sides \(16\) and \(13\)).

Then we can think of this smaller rectangle as being composed of one square (of side \(13\)) and another yet smaller rectangle (with sides \(13\) and \(3\)).

Then we can think of this yet smaller rectangle as being composed of four squares (of side \(3\)) and a rectangle (with sides \(3\) and \(1\)).

Finally we can think of this tiny rectangle as being composed of three squares (of side \(1\)) which completes the decomposition.

This is the same as observing that \(\cfrac{45}{16} = \cfrac{(2 \times 16) + 13}{16} = 2 + \cfrac{13}{16}\)

that \(\cfrac{16}{13} = \cfrac{(1 \times 13) + 3}{13} = 1 + \cfrac{3}{13}\)

that \(\cfrac{13}{3} = \cfrac{(4 \times 3) + 1}{3} = 4 + \cfrac{1}{3}\)

By inverting the above we can see that \(\cfrac{13}{16} = \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{3}{13}}\)

and that \(\cfrac{3}{13} = \cfrac{1}{4 + \cfrac{1}{3}}\)

Substituting these back into our first equation we can finally get …

\[\cfrac{45}{16} = 2 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{1}{4 + \cfrac{1}{3}}}\]… where the numbers are the counts of squares in the decomposition of the 45 by 16 rectangle.

Continued Fractions for Irrational Numbers

A rational number will always have a terminating continued fraction but what about an irrational number? Let’s think about the first irrational number that people usually learn about, namely \(\sqrt{2}\).

If we start with the obvious identity \(\sqrt{2} = 1 + (\sqrt{2} - 1)\) then we can further see that \(\sqrt{2} = 1 + (\sqrt{2} - 1)\cfrac{(\sqrt{2} + 1)}{(\sqrt{2} + 1)}\) and then multiply out to get \(\sqrt{2} = 1 + \cfrac{(2 - \sqrt{2} + \sqrt{2} - 1)}{(1 + \sqrt{2})} = 1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \sqrt{2}}\)

This recursive identity for \(\sqrt{2}\) can be expanded …

\[\sqrt{2} = 1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + 1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \sqrt{2}}}\]and expanded …

\[\sqrt{2} = 1 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \cfrac{1}{1 + 1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \sqrt{2}}}}\]We can see that this results in an infinite continued fraction with the following pattern …

\[\sqrt{2} = 1 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \ddots}}}}}\]The sequence of numbers in a continued fraction like this is often written more concisely as …

\[\sqrt{2} = [1:2,2,2,2,2,\dots]\]It is true that all irrational numbers will have an infinite continued fraction. Here are some other examples …

\[\sqrt{19} = [4;2,1,3,1,2,8,2,1,3,1,2,8,2,1,3,1,2,8,2,\dots]\] \[e = [2;1,2,1,1,4,1,1,6,1,1,8,1,1,10,1,1,12,1,\dots]\] \[\phi = [1;1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,\dots]\] \[\pi = [3;7,15,1,292,1,1,1,2,1,3,1,14,2,1,1,2,\dots]\]These sequences are, respectively, A040000, A010124, A000012, A003417 and A001203 in the wonderful Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences.

There’s some structure here too. The sequence for \(\sqrt{19}\) repeats the sub-sequence \(2,1,3,1,2,8\) indefinitely with period \(6\). The sequence for \(e\) repeats the sub-sequence \(1,n,1\) indefinitely with \(n\) starting as \(2\) and then increasing by \(2\) each time. The sequence for \(\phi\) is probably the simplist of all. However there is no currently known structure to the sequence for \(\pi\) which makes it all the more special.

The Continued Fraction for \(\pi\)

I propose that the sequence of integers in \(\pi\)’s continued fraction is a much better thing for people to focus on than the digits of its decimal representation. This sequence has nothing to do with a choice of base and is truly indicative of the fundamental structure of probably the most famous number in all of mathematics.

The Continued Fraction for \(\sqrt{x}\)

We can generalize what we did above for \(\sqrt{2}\) …

\[\sqrt{x} = 1 + (\sqrt{x} - 1)\] \[\sqrt{x} = 1 + (\sqrt{x} - 1)\cfrac{(\sqrt{x} + 1)}{(\sqrt{x} + 1)}\] \[\sqrt{x} = 1 + \cfrac{(x - \sqrt{x} + \sqrt{x} - 1)}{(1 + \sqrt{x})} = 1 + \cfrac{x - 1}{1 + \sqrt{x}}\]Thus …

\[\sqrt{x} = 1 + \cfrac{x - 1}{2 + \cfrac{x - 1}{2 + \cfrac{x - 1}{2 + \cfrac{x - 1}{2 + \cfrac{x - 1}{2 + \ddots}}}}}\]The recursive relation above makes for a very nice recursive algorithm for the calculation of square roots to a given level of precision.

Rational Approximations to Irrational Numbers

We can use these sequences to construct successively better rational approximations to an irrational number and, in the case of \(\pi\), some familiar rational approximations fall out. We do this by truncating the continued fraction at successive levels and assuming that the remaining fractional part is zero. Starting at the top we have …

\(\pi\)

\[\pi = 3\]The most basic approximation and not a very good one. \(\pi - 3 = -1.42 \times 10^{-1}\), an error of \(-4.5\%\).

\[\pi = 3 + \cfrac{1}{7} = \cfrac{(3 \times 7) + 1}{7} = \cfrac{22}{7}\]A familiar old approximation and reasonably accurate. \(\pi - \frac{22}{7} = 1.26 \times 10^{-3}\), an error of \(0.04\%\). We can do better though.

\[\pi = 3 + \cfrac{1}{7 + \cfrac{1}{15}} = 3 + \cfrac{1}{\cfrac{(7 \times 15) + 1}{15}} = 3 + \cfrac{15}{106} = \cfrac{(3 \times 106) + 15}{106} = \cfrac{333}{106}\]\(\pi - \frac{333}{106} = -8.32 \times 10^{-5}\), an error of \(0.00265\%\). Let’s keep going.

\[\pi = 3 + \cfrac{1}{7 + \cfrac{1}{15 + \cfrac{1}{1}}} = 3 + \cfrac{1}{7 + \cfrac{1}{16}} = 3 + \cfrac{1}{\cfrac{(7 \times 16) + 1}{16}} = 3 + \cfrac{16}{113} = \cfrac{355}{113}\]A particularly good approximation for \(\pi\) since the presence of the number \(292\) as the next element in the sequence ensures that the residue after truncating the continued fraction at this point is quite small. \(\pi - \frac{355}{113} = 2.67 \times 10^{-7}\), a tiny error of \(0.0000085\%\) and basically zero for all practical purposes.

\(\phi\)

The continued fraction for \(\phi\) (The Golden Ratio) may seem trivially simple but actually it makes this number all the more special. It can be considered the most irrational of irrational numbers because it is the most difficult to approximate with a rational number.